Table of contents

I Research in NAIP

I.a Rationale: Why Research?

I.b Reflective Practice and Research

I.c Reflexivity and the Researcher

II Approaches & Practical Examples

II.a Exercising Reflective Practice

II.b Students' Biographical Self-reflection

II.c Portraits of NAIP Students

II.d Research Approaches and Types

III Coaching Research

IV Literature lists

V.a Research and NAIP Concepts

V.b Methodology

V.c Critical Studies

V.d Literature for Coaches

V Reader

II Approaches & Practical Examples

II.a Practising Reflection and Research

Reflection and research sometimes seem to present difficulties for musicians. While they may make total sense in theory, the reality is that they may feel distant from the actual practice.

The challenge then is to find ways to make reflection and research come alive as an integrated and central part of musicians’ professional and personal practice. This is perhaps where understanding the connections between reflection and research become so important. It may be helpful to start by recognising ways in which individuals are already engaged in processes of questioning, experimenting and reflecting, even if on a very small and personal level. How does this actually happen, where do individuals find energy in doing so, what do they learn from it? It can be invaluable to get a sense of ones existing strengths and preferences, and ways in which these may illuminate the fact that reflection and research are not completely alien, outside existing experience.

Then comes the opportunity to start to grow and deepen such practices to something more powerful, insightful beyond our personal development, something more systematic or collaborative, that can guide development and innovation further. Research will be the essence of this process.

Examples

The following examples offer practical tools and forms for reflection that may be valuable as part of a reflective or research process. Each one can yield important insights and may indeed generate material that is used as part of a research process. An important issue to recognise is that both reflection and research can have individual and collective elements.

It is important to note, however, that for example a reflective journal will not constitute the output of research. When a research journal is used within research it creates material which will then need to be analysed, or specific insights will need to be drawn out of it.

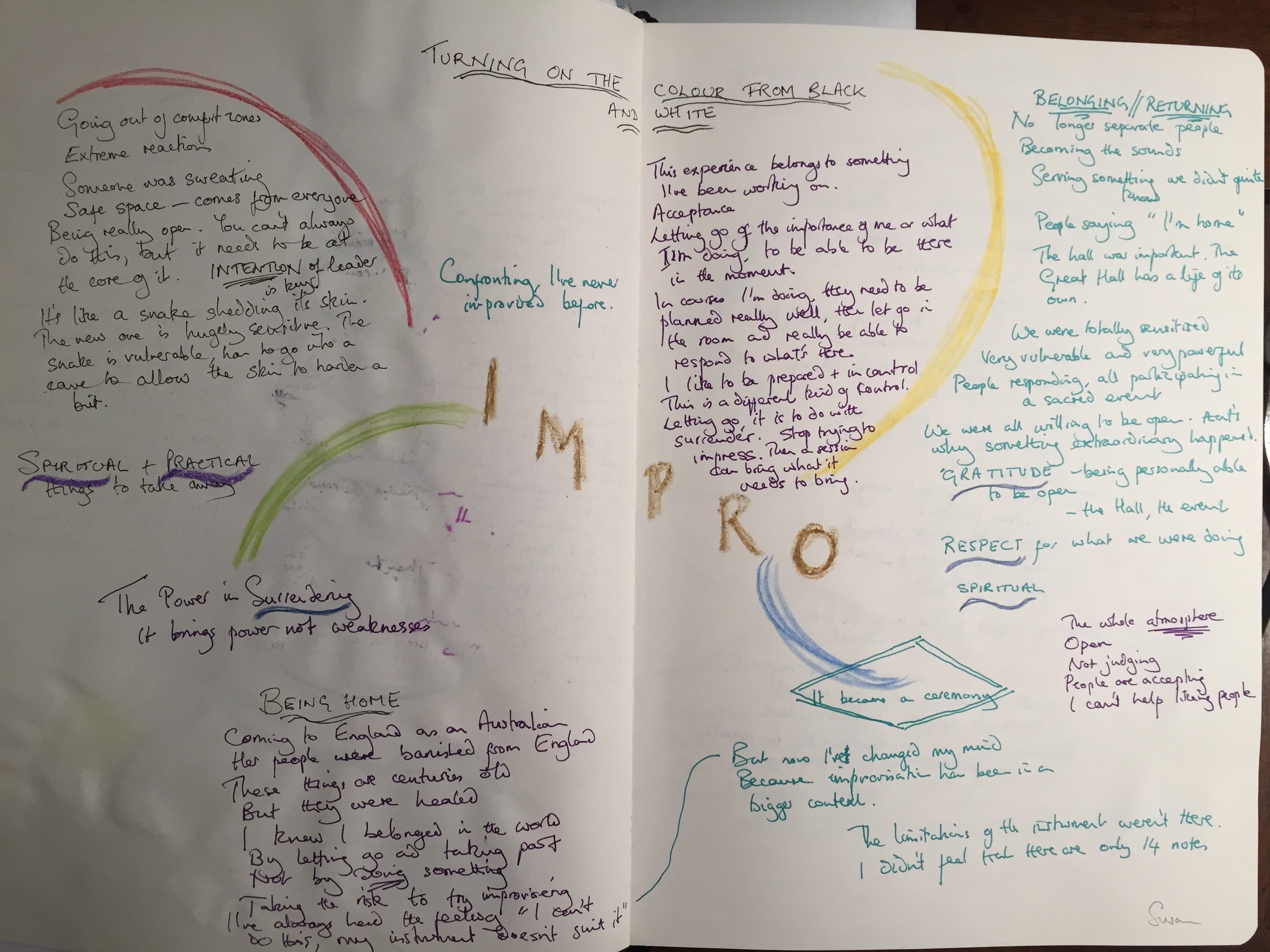

Mind-mapping reflections

This is a process that can be done individually or, for example with a coach/peer mentor. Taking a particular event or issue, or indeed research question, the working form creates an opportunity to set out thoughts on different aspects of the issue. These might include personal reflections on experiences, connections to literature or other contextualising materials, conceptual ideas or further questions arising etc.

The following example comes from a conversation undertaken by Helena Gaunt (Guildhall School of Music & Drama) with a participant in the Innovative Conservatoire about their experiences of improvisation in the seminar and its relevance to professional practice.

Performer’s loop

Performer's loop overview

Performer's loop self assessment

This is a reflective process that has been designed to support thinking through one’s own performance in a particular context. It was devised by Robert Schenck at the Gothenburg Academy of Music and Drama, Sweden, as an innovative way to enable musicians to reflect on their performances, individually and collectively. We know, very often that performing can generate strong emotional responses when we are the person performing, and that these emotions may have a powerful impact on us (either positively or negatively) and equally in ways that cloud our ability to see things from a more objective or rational perspective. We can get stuck in the emotion, and then find it difficult to move on and into exploring new goals.

This working form acknowledges and honours an emotional response to performing. Indeed this forms the first step in the process. Undertaking first step then opens the space for other, more objective perspectives to be seen and heard and given due consideration. The Performer’s Loop is a form that can produce some profound insights and liberate individuals to learn from their experiences and move into new territory.

The following paragraphs provide further insights and practical detail about this working form from the author Robert Schenck:

For several semesters I worked on nonjudgmental self-evaluation with groups of Master students. (In essence, we did only steps 2 and 3 on the form.) After a while, I realized that a good number of students had all these emotions (of course) and even though I acknowledged them, I, in a sense, dismissed their feelings because "I feel so disappointed after the audition." or "I am so ecstatic." are 1. close to being judgmental ("I played so badly." or "I played so well.") and 2. do not give any information that enhances my further work.

Dismissing feelings, as they felt I was doing, is never good, so I then added the first step: yes, these feelings are huge, and feelings are always true and important to the person feeling them. It's the feelings after the performance that are to be written in step 1. (Either feelings I remember having directly afterwards, or feelings I have at the time of filling out the form.) Write them all down in step 1, they are important to acknowledge. Let your feelings reign, this form is anonymous if you wish it to be. These feelings are also important to "get around" in order to be able to be nonjudgmental in step 2.

So the purpose of step 1 is to let yourself feel; whatever you feel after the performance is OK, and after writing them down go ahead to step 2. Often, by acknowledging and accepting in step 1, you will be clearer in your answers in step 2. According to Timothy Gallwey, the less judgmental you are, the more accurately you will remember what actually happened (and thereby will maximise your learning and advancement).

The performer may also remember feelings he/she had AT the performance. If desired, these should be expressed non-judgmentally under step 2. If one notices non-judgmentally that a a feeling for instance got in the way during performance then the chances of being able to see that clearly and avoid that next time will increase. (Let's say there was a certain person on the jury or in the audience who awakened fear in me. Under step 3, I can consider ways of preparing myself mentally before my next performance in order to reduce the chances of the fear recurring.)

Here are some examples of typical answers under the three steps if the form is filled out "correctly", thereby maximizing its usefulness:

1.

I am so angry.

I am so pleased with myself, ecstatic.

I feel so unhappy and disappointed.

2.

I was sharp in the upper register.

I played no wrong notes in the technical passages that I had practiced most.

I was concentrated throughout the entire performance.

I experienced the piece as a whole for the first time at the performance.

I became much more concentrated after the interval.

As soon as I saw her in the audience I tensed up and stopped listening.

During the performance the feeling of flow filled me with joy.

3.

When preparing for my next audition I will ... (preferably tactics based on observations in step 2)

I will not eat dinner before my next concert.

etc...

I may add one thing: I usually say to someone that has very positive feelings in step 1 to retain the energy they give you. Keep on feeling good and remember those feelings! To the person who is terribly disappointed I advise to let yourself feel that way for a limited amount of time, acknowledge it as natural, and do not repress it immediately. But as you go on to step 2, and on in your continued practice, wave good-bye to those negative feelings and let them go their merry way. They don't offer you constructive energy.

GROW model

This is a structured reflective process that comes from executive and life coaching work. It has a future focus and is designed to result in specific commitments being made to action. There are four stages in the process, each of which takes the conversation in a particular direction:

Goal

Reality

Options

Will (and what, when and with whom)

Each stage is supported by a series of open questions. These are indicative rather than mandatory. In the early stages of getting to know the process, it can be helpful to use them precisely.

It is important here to follow the stages of the process closely and not jump to the concluding parts before the first stages have been worked through in some detail. It is a process that individuals can follow for themselves, working through the questions. It is often even more productive with a coach who can follow up and go further into the questions that elicit significant responses. Students can develop skills as peer coaches for one another, although it is important to recognise that the art of open questions and of allowing the respondent to find their own solutions rather than offering them advice and the coach’s solutions takes practice.

The process is likely to be particularly valuable for using with, for example, career development questions, or when specific challenges are encountered in a project.

Critical Response Process

This is a collective feedback process devised by dancer and choreographer, Liz Lerman, for use with creative work in progress. It focuses on creating generative and formative feedback, with the artist at the centre of the process, that will inspire and empower the artist to go back to work. In reality the process can also be a wonderful way of enlarging everyone’s experience of a piece of work, and can help to hone important collaborative skills for artists. This is an approach that, once mastered, can become more of a way of life, informing one’s attitude and approach to interactions of many different kinds.

The full Critical Response Process has four specific steps:

Statements of meaning

Artist’s questions

Neutral questions from the responders

Opinions

Once familiar with these steps, all kinds of variations can be made to suit different situations, number of people involved and time available.

Further information: https://lizlerman.com/critical-response-process/